Skyrim vs. Witcher 3, part 2: Morality

Open-world RPGs are primarily about exploration and customization. They present players with a series of decisions, which allows the player to customize the world of the game, the character they control, or both. In the last post, I talked about how the player is (or isn’t) allowed to change the world of the game - so now let’s talk about how players can shape their character.

A lot of character customization in RPGs happens iteratively over the course of the game. You may be able to pick some traits at the beginning, but after that you’ll adjust your attributes through gameplay - doing stuff like leveling up, increasing stats, adding new companions to your adventuring party, getting better gear, etc.

Over the past few decades, it’s become increasingly common to allow players to customize their character’s personality as well, often including their morality. This isn’t new, or specific to RPGs - lots of story-driven games have you make decisions to determine whether you get the “good” ending - but open-world RPGs have been focusing heavily on morality as a gameplay feature, dedicating entire systems to representing your character’s ethics both mechanically and aesthetically.

In fact, different approaches to morality have become part of the brand of certain game developers. Both FABLE (made by Lionhead Studios) and FALLOUT 3 (made by Bethesda Game Studios) started out with a simple “good versus evil” meter, but just added a bunch of other meters in their sequels: FABLE 2 had things like “Corruption versus Purity” (i.e. “Are you evil, but kinda half-assed about it?”), and FALLOUT 4 replaced the single “Karma” meter with one for each of your individual friends representing what they think about you. Meanwhile, games like JADE EMPIRE and MASS EFFECT (both made by BioWare) theoretically used their own, setting-specific moral axes instead of “good versus evil” ("Open Palm versus Closed Fist" or "Paragon versus Renegade", respectively). Both the Lionhead games and the BioWare games also change your character’s external appearance to reflect your inner morality - indicating “darker” decisions by having you grow literal devil horns, or by having your eyes and scars start to emanate a crimson glow, for example.

Someone in 2001’s JADE EMPIRE explains that the world isn’t as simple as “good” and “evil” - instead, it’s more like these other two mutually-exclusive moral options

This is what you look like in 2010’s MASS EFFECT 2 if you’re far enough on the “Renegade” track. Also, you sometimes say racist things like this. But it’s totally not “evil”, we promise

I’m not gonna go into the evolution of these implementations of morality-as-a-game-mechanic, not just because that could be a whole article unto itself, but also because WITCHER 3 doesn’t really follow any of these approaches. And, despite being developed by the same studio as FALLOUT 3 and 4, SKYRIM is actually a bit more like WITCHER 3 than those two (kinda (sorta)).

You know what game might characterize WITCHER 3’s approach better than its mainstream open-world RPG peers?

PAPERS, PLEASE is an indie game where you play as a border official for a fictional Eastern European nation. Each day, you review the documentation of everyone trying to enter the country through your checkpoint, and decide who to approve and who to reject. The game presents you with an endless torrent of moral decisions, but it never tracks your “morality” explicitly. There’s no meter - only the choices you make, and the consequences they build towards.

Someone whose fingerprints don’t match their documentation pleads with you to be allowed past a border checkpoint

Similarly, WITCHER 3 has no “morality meter”. It presents you with tons of moral choices, too, but there’s no discrete mechanic underlying them - the payoff for your decisions is specific to the decisions themselves, and they add up to your overall characterization of the guy you play as in WITCHER 3 (a dude named Geralt). Technically, this is also the way things work in SKYRIM, but, well…we’ll get to that.

Now, morality in video games is a topic that’s so common and seems so intuitive that we’re going to have to define it a bit before jumping into this thing.

In a game like MASS EFFECT, “morality” is actually more about choosing which media archetype of a hero you want to represent, as is reflected in the name of their two moral poles (“Paragon” and “Renegade”) as well as the fact that the game tracks being gruff in dialog the same way it tracks literal murder. MASS EFFECT may have much better writing than, say, FALLOUT 3 (where one of your “moral decisions” is “do you you bomb the second-most-populated town in the map just because someone says they think it looks ugly”) - but ultimately, neither game’s system for dealing with morality is designed to encourage something like self-reflection on the part of the player.

So, when I say I want to evaluate SKYRIM and WITCHER 3 in terms of how they approach “morality”, I want to focus on two things in particular:

How they let you express yourself morally

How they make the moral decisions meaningful to the player

On top of that, I’ll mostly limit myself to moments and mechanics specifically intended to highlight moral decisions. That is, I’m sticking to quests that explicitly present you with a choice to make.

I’m not saying that this is the only or best way to talk about “morality” in these games. There’s plenty of other things to consider in that broader conversation (like, “does the game expect you to kill humanoid enemies with families and friends and dreams by the dozen, without batting an eye?”), and they’re worth considering. I’m not going into them here, though, both to focus on ways that SKYRIM and WITCHER 3 are different, and to limit the scope of what we’re talking about so that this article comes in at a reasonable length (stop laughing).

With that said, let’s jump into the first topic: How do each of these games let you express yourself through the moral decisions they present you with?

All-you-can-eat Ethics

Like last time, I’m going to start by comparing a couple of representative quests from each of them, starting with one from SKYRIM called “With Friends Like These…”:

At the beginning of the quest, you find yourself locked in a shack with an assassin and three hooded & bound victims. The assassin tells you that one of them has been marked for death, and tasks you with interrogating each of them and then killing the right one. The assassin won’t let you leave until you kill at least one of them - after which, you get invited to join a death cult called the Dark Brotherhood, which opens up a whole questline to ascend the ranks through contract killings.

At first, it looks like you only have three options to choose from. But there’s a fourth option: Kill the assassin. If you do that, you get an entirely different (though much shorter) questline to destroy the Dark Brotherhood. This is, in a vacuum, a fine enough sort of “moral decision point” to have in an open-world RPG. You have two different ways you can interact with the Dark Brotherhood, and each path has its own associated content. Exploration and customization.

But most decisions in SKYRIM don’t work like that. Most of them work like they do in another quest - “Boethiah’s Calling”.

This quest begins when you discover a cult that worships Boethiah, who is essentially the demon-god of betrayal. In order to join the cult, you are tasked with bringing a friend to the ritual altar and murdering them. This is, fundamentally, the same hook as “With Friends Like These…” - you’re asked to kill someone to join a creepy murder club - except this time, you basically can’t say “no”.

I mean, yes, of course, you could just not…y’know…murder one of your friends. No-one’s forcing you. But the quest stays open in your quest log until you do. You can’t “close” the quest. Even killing all the Boethiah cultists doesn’t do anything. Unlike “With Friends Like These…”, there’s only one path to more content. You’re either playing the game as intended, or ignoring it. That’s not an actual choice.

Even the design of the location pushes players on: The shrine of murdering-your-friends is adorned by an epic sculpture, it magically turns to night when you approach it, and the sky fills with majestic lights. This is an exciting, enticing visual; if you enjoy playing high fantasy games like SKYRIM, this is exactly the sort of thing you seek out, not avoid. They made this thing for you to want to interact with, but they only made one way to interact with it.

“So, do you want to kill one of your friends for no reason now? …No? Hey, that’s cool, no pressure. I’ll just check in with you later, see if you change your mind, y’know, next time you decide to stop by my dope fantasy shrine. Dedicated to murdering your friends.”

SKYRIM isn’t asking how you want to represent yourself morally, it’s asking if you want more content or not. Which is part of why the game eventually brings players to an “eh, fuck it” level of engagement where they’re just as likely to bomb an entire town as not.

You even see this bear out in discussions by people who really enjoy SKYRIM. For instance, check out the top answer in this thread I found on Reddit while looking up what people thought was “the toughest moral choice in SKYRIM”:

Screenshot taken on June 16th, 2021

The quest they’re talking about here is called “Waking Nightmare”. It revolves around a priest who was kidnapped into a cult that worshipped another evil demon-god, but has since repented and wants to destroy an artifact that is inflicting a plague on the surrounding land - an artifact that is literally called the Skull of Corruption, in case you thought there was any ambiguity or complexity in this scenario. Just before the Skull is destroyed, the evil demon-god commands you to kill the priest (this is their only line of dialog in the entire game), and you have to make your decision:

If you don’t kill the priest, they destroy the Skull and the quest ends (the priest becomes a friend - the kind you can sacrifice for “Boethiah’s Calling” - but they’re not mechanically noteworthy).

If you do kill the priest, you get to keep the Skull (a weak weapon with gimmicky mechanics) and the quest ends.

That’s it. “Kill a good person who is trying to help people, so you can get a toy, or…don’t…do that.”

But for some people, that was a major moral dilemma. And it’s not because these people are psychopaths - it’s because they recognized, on some level, that a game they’re enjoying is asking them whether or not they want more content. And whatever your idea of morality is, the default answer to that question is “yes, obviously, that’s why I’m playing the game”.

There’s another element in that Reddit post that’s also telling: After the author decided to forgo the Skull, they had the priest join them on their adventures. This priest isn’t useful or powerful or interesting; there’s no payoff for having them around - they don’t even have any dialog referencing their shared adventure in “Waking Nightmare”. The relationship with the player is purely in the player’s head. In other words: When the player opted out of getting additional game content, they were forced to invent the content that the game didn’t give them for choosing what they did.

You the the same impulse in a lot of fan-made mods for the game, too - for instance, there’s a bunch of mods that let you complete “Boethiah’s Calling” while still being a “good guy”. (Hilariously, though, most of these mods just involve creating some new character that’s made specifically to be sacrificed, so you don’t have to feel bad about sacrificing a friend.)

OK, I still don’t want to call these people psychopaths, they’re still just reacting to the incentives laid out by the game’s developers and writers…but…uh…I think I have a different definition of “good guys” than they do

So, what’s different in WITCHER 3?

For one, their quests give you a lot more options. This sometimes means more outcomes, but it doesn’t have to.

In the last article, I mentioned an early quest where you can turn an arsonist over to the authorities - but there’s two different ways to take them in: you can beat them up, or you can subdue them magically (i.e. nonviolently). Both of these options lead to the same outcome, which in this case is the arsonist’s death, but giving you these options still affords the player the ability to customize their characterization of Geralt (the person they’re controlling): Does he happily serve out beatdowns whenever someone gets lippy, or does he prefer nonviolent solutions?

An even better example comes at the end of a quest called “Following the Thread”. One of Geralt’s friends asks for help tracking down the person who killed someone close to him. When the two of you finally confront the killer, they claim that the death was not their doing, and have spent the past several years making a new life for themselves - including starting a loving family.

You can choose to hear their side of the story, purely to see if the information helps you make up your mind. Whether you listen to it or not, you get four options:

Believe that they’ve changed, and aren’t the same person involved in the death.

Accuse them of faking repentance and being a cold-blooded murderer.

State that it doesn’t matter whether they’ve changed or not, they still have to pay.

Decide you don’t want to have to sort out the truth, and walk away.

Your choice leads to some dialog with your friend (who just wants to gut the killer), and then you have to make the same choice again, but this time with only two options: kill him or spare him. This quest doesn’t just let you make a moral decision, it makes you affirm the consequences of your decision - or else change your mind. And even though you’re ultimately just choosing between two outcomes here, you get to choose your reasoning for them. And that isn’t just in your head, filling in the blanks left by the lack of intended play experience - it’s fully rendered, in-game, with voice acting and everything.

Your buddy knows which choices he wants you to make

As an added wrinkle: Geralt is always accompanied by his friend, Lambert, who wants the guy dead. So even if you choose not to spare the killer, you can actually just stand back and let your friend have his own vengeance, if that makes a moral difference to you. Normally, I’d count this as a quirk of gameplay, not something about the structure of the quest (and therefore the moral options presented to the player explicitly by the game’s writing), but in this case it’s clearly intentional: some of the dialog has Geralt outright tell Lambert that it’s up to them to actually do the deed.

And this is just a quest with two outcomes; there’s plenty of quests in WITCHER 3 with more outcomes than that (by contrast, I can hardly think of any in SKYRIM).

Between having more outcomes for quests and having more options within quests, the player gets to express their morality through gameplay in a lot more detail in WITCHER 3.

There’s an additional payoff to the buffet of moral decisions, though, beyond just getting to characterize Geralt in more detail. Having to make so many of these choices does a lot of work to frame how you think about and approach the important choices in the game - because it makes it harder to tell what the important choices are.

To show why that’s a good thing, let’s take a quick look at a bad game. In this case, SILENT HILL: DOWNPOUR. Like the earlier games in the Silent Hill series, DOWNPOUR has multiple endings - some “good” and some “bad” - and which ending you get depends largely on the narrative choices you make.

The problem is that there’s only three key decision points, and they look like this:

I wonder which choice will move me closer to the “good” ending

Because these decisions are so obvious and so few, they don’t invest you in the choice you are theoretically making for the character. Your engagement stays at the surface level.

By contrast, when you have to make moral decisions constantly (and they have clear consequences), you are more likely to give each choice more consideration. When the choice isn’t clearly as simple as “which ending do I want” or “do I want to get a special skull”, you pay attention to the choice on its own merits. The reason to listen to the man that you and your friend want to kill isn’t to get a reward - it’s to get more information to figure out which choice you feel is right.

And now we’re getting to another major component of this discussion - how the game gets you to care about getting these choices right in the first place. It’s easy to say it’s all just down to which game has “better writing” or “better performances”, but there’s actually an underlying structural approach to payoff for all these decisions that’s different in WITCHER 3 from SKYRIM.

Just desserts

Let’s talk about FALLOUT 4 for a hot sec. FALLOUT 4 was made by the same studio as SKYRIM, and released in the same year as WITCHER 3.

As I mentioned before, FALLOUT 4 has a list of characters that can become the player’s companion, and each of them has their own morality meter (called “affinity”) that tracks what they think about you based on your actions. Different companions care about different things - some think stealing is rad while others hate it, some really only care about building neat shit in your garage, and one is a dog that loves you no matter what you do. If a companion’s affinity score gets high enough, they give you perks like “you take 20% less damage” and can become romantic partners; if a companion’s affinity score gets low enough, they might permanently turn against you.

The game directly tells you what your companion’s reaction (if any) is to your actions as soon as you do them. Immediately after you choose a certain dialog option or whatever, a message like "Valentine liked that" or "Piper hated that" appears.

From a gameplay perspective, this is a helpful feature. The companions are basically virtual pets which can confer gameplay rewards under the right circumstances, so it's useful to know immediately whether you're successfully “raising” them to that point.

But the cost of this is...well...that your companions are virtual pets.

The actions you do to please your companion never really feel sincere or meaningful. Even if they’re things that you actually want your character to be doing, the game is telling you that the only reason why any given moral decision matters is that it affects your companion's affinity score. When I played FALLOUT 4, one of my companions for most of the playthrough was a pretty upstanding dude, and so to boost his affinity I would try to be an upstanding dude myself. And when I do would do good deeds and they didn’t raise his affinity, I would get annoyed - and moments like that make it real clear what motivators I’m actually responding to.

(This system also leads to some really goofy moments where, for instance, a companion who is morally opposed to lockpicking is trying to kick down a door, and if you pick the lock on the locked door they were trying to open, you lose affinity with them.)

This is worsened by the fact that all these actions are completely fungible - that is, they’re reversible and interchangeable. Was Valentine upset when he watched you murder someone (-15 affinity)? No matter, just tell that old hippy to lay off the drugs (+15 affinity), and you’re square. Instead of building long-term relationships with memorable characters, it feels like you’re playing babysitter for a bunch of robots with anterograde amnesia.

OK Valentine, how many Hail Marys do I owe you to wipe away that side-eye?

And in this regard, despite not having an explicit morality system, SKYRIM very much follows in the footsteps of Bethesda’s Fallout games: The consequences of your decisions are immediately clear, and then immediately forgotten. Did you kill the priest in “Waking Nightmare”? Cool; take your magic skull and move on with your life - no-one’s ever going to bring it up again. All the “payoff” is instantaneous - to the extent that it hardly feels like “payoff” at all. It’s like signing up for a five-course meal and only getting the dessert. And dessert’s tasty, but where’s the rest of it? Where’s the buildup?

These features also contribute to the “eh, fuck it” attitude towards moral decisions in the game: As soon as you make the choice, you see what the outcome is, and if you don’t like it you just load a save file from 5 minutes ago and choose differently. Exactly like the Reddit answerers said they did for what they thought was the “biggest moral dilemma” in the game. The deepest that SKYRIM can get you to engage with a moral decision is going “wait, no, let me try that again”.

It doesn’t make sense for me to list specific quests in SKYRIM to illustrate this, because they all work like that. The closest thing to any delayed payoff or downstream consequences for quest decisions is when major stories overlap - like when the main questline requires you to negotiate who gets to occupy certain territories, which depends partly on where you are in the war-with-the-empire questline.

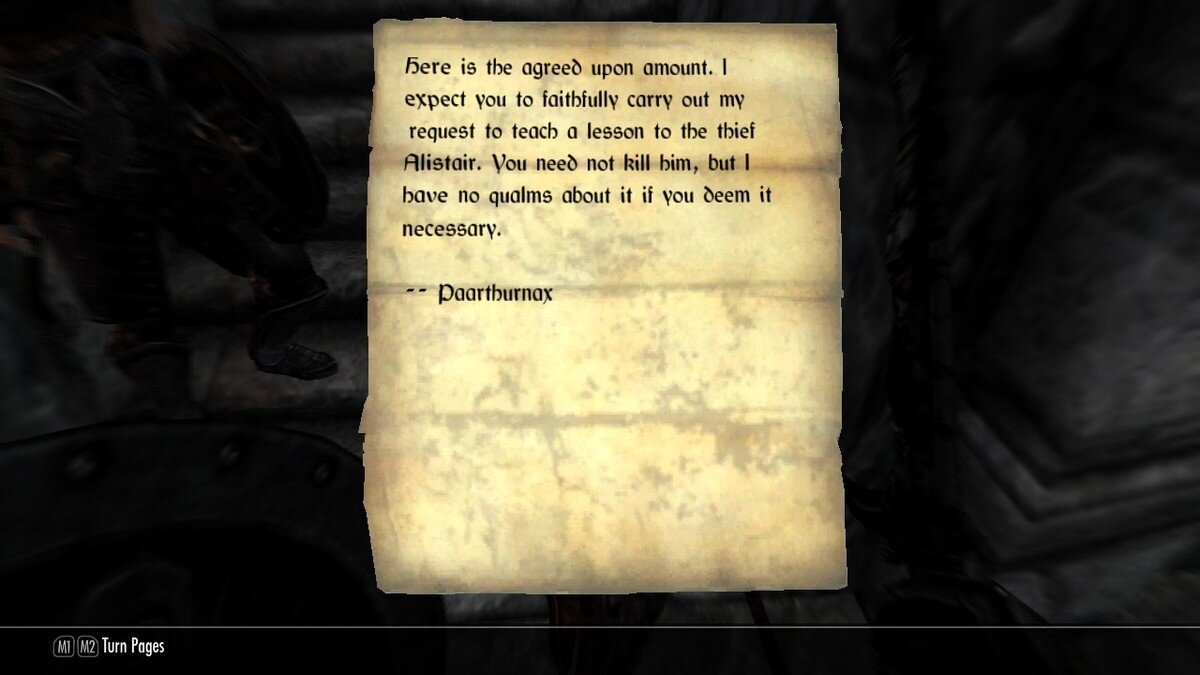

Outside of quests, SKYRIM sometimes has delayed consequences for your behavior. If you rob someone, for example, you might get assaulted by a thug later on that was hired by the person you robbed to teach you a lesson. This is cool the first time it happens, partly because it’s just so stunning that one of the cardboard cutouts with a voicebox that populates SKYRIM actually noticed you doing something without the game immediately telling you. It’s not like you’re shocked to learn that people will be upset if you rob them - it’s that you’re shocked that they even noticed.

Oh, also, while I was double-checking how this system worked when writing this, I discovered that the list of characters who can hire thugs is hilarious. One of them is Paarthurnax, who is a pacifist dragon who never leaves his home on top of the tallest mountain on the continent and whose existence is kept a secret to all but a reclusive society of nearly-mute monks who also live on that mountain. He’s also your personal mentor in your quest to defeat the evil dragon that is fated to devour the world. And the note his thugs carry has the exact same template as every other one.

What did Paarthurnax even pay the thugs with? Steam credits to buy SKYRIM mods where this shit doesn’t happen?

So…am I actually saying that it would be better if the game didn’t tell you all the outcomes of your decisions immediately? If it made you have to eat all your veggies before giving you dessert?

Well, yes. At least, if it wants you to be invested in them.

Narratively, payoffs are often more powerful if more time has passed since the set-up - that’s part of why comedians frequently work a callback to an earlier joke towards the end of their routines. But there’s a mechanical reason why delay makes the payoff more significant, one that’s specific to video games:

You can’t load an earlier save file and undo your decision.

If you make a choice to spare someone’s life, and then after hours (or even days) of gameplay they turn out to do something terrible, chances are slim you’re going to load a save file from before you saved their life, and lose all the progress you’ve made in the meantime. No, you’re stuck with it now. And you know what? That’s a good thing in this case. Because it makes the decision matter. This is the essence of what made it cool in SKYRIM the first time you found out someone held a grudge against you for robbing them - but WITCHER 3 turned it into an entire, well-conceived structure for how the game approaches moral choices.

After the first time you face consequences you didn’t want for a choice you made last week, you’re likely to make every subsequence choice more carefully. Maybe more sincerely, too - since the inability to trivially change the outcome (by loading an earlier save or by bribing someone with unrelated good deeds) makes these moments more effective at prompting some limited amount of genuine reflection on the part of the player.

But “self-reflection” doesn’t have to mean “guilt”. In fact, I’m more impressed if a game can make me feel proud of decisions that I can attribute to my own character, in a way that feels genuine and earned - rather than just patting me on the head for something every player controlling the protagonist would do, like saving the world.

And to show you how WITCHER 3 pulls that off, I’m going to spoil one of my absolute favorite side-quests from the game, because there’s no way to discuss meaningful long-term payoff to moral decisions without spoiling something.

Before we get to the quest, some quick context about the game:

In WITCHER 3, you play as Geralt of Rivia. Geralt is a type of specialized monster hunter called a witcher - one whose skills are as indispensable as he is reviled by most of society. A lot of the side-quests in the game are contracts where people hire you to kill some monster: you use your supernatural senses to track the creature, your expertise in all things inhuman to understand what’s really going on, and then you fix the problem so you can get paid. These contracts can go a lot of different ways. Sometimes the monster isn’t what you were told it was; sometimes you uncover someone’s dirty laundry over the course of the quest; sometimes you arrived too late to save someone from the monster.

And sometimes you might decide the monster doesn’t need to be killed at all. Some of these creatures are thinking, feeling beings just like people. Some, like werewolves, are people. And even in this subset of contracts, there’s a variety of situations to resolve. If people die from accidental contact with a monster who means them no harm, how do you assess its innocence? These sorts of contracts are great.

And sometimes, the monsters hurting people happen to look like human children, too. And might not know what they’re doing.

A lot of the time, though, you’re just killing snarling beasts.

So, pretty far into the main story of WITCHER 3, you might take on a quest called “Skellige’s Most Wanted”. This is a witcher contract, and it begins like so many others: someone hires you because their wagon got attacked by a band of feral monsters, and they want you to kill the monsters. As you investigate, the clues don’t add up, and it quickly becomes clear that the contract was a set-up to try and kill you. After you thwart a few deathtraps, you go to confront the schemers behind it - and discover that they are a group of monsters.

After all, you are a famous monster hunter. You are their boogeyman. But this quest is more special than a simple “OMG, are you the real monster??” twist - because you get to talk to them, as they figure out what to do with you.

You can, of course, draw your sword and get down to business - they wanted to kill a witcher so bad, they can come and try, right?

But you can also try to tell them that you are actually one of the few people in a position to protect monsters. The people hiring Geralt don’t understand monsters the way he does, and if they had their way, far more monsters would be needlessly killed. Geralt is in a position to exercise the discretion that the general populace cannot. As you explain this, Geralt recounts moments from the original books that the games are based on, where he helped dragons and other creatures.

But that’s not good enough. The monsters demand more.

And at that point, the game showed me something I didn’t expect: a chronicling of my own past decisions, as the player. For each time I actually chose to help a monster in a quest, there’s a unique dialog option to tell the story of how and why I helped them.

Here is a fully-rendered, fully-voice-acted cutscene in which Geralt is recounting the decisions that I made - me, the player - totally independent of this outcome, but relevant to what's happening now!

And as if that wasn't wonderful enough, one story isn’t enough to sway the group. So it's not even as simple as “do this one quest one way to unlock this outcome later” - the game is aggregating the outcomes of multiple different totally unrelated quests over a large span of time, encountered at totally different moments of the game.

There's no morality score in WITCHER 3. No affinity score. No message telling me "Monsters liked that" when I chose to spare them. I chose what I did because it felt right, and I made similar decisions in similar circumstances, and I thought that was it. I made those decisions for their own sake, only to later find myself in a situation where the outcomes of those decisions mattered - and the game treated me to a visual, narrative reward for them.

But wait, there’s more!

When I saw the list of my acts of mercy in those dialog options, it made be realize that there were other moments that should’ve been here…if I had chosen differently. I thought back to the contracts where I wasn't as generous, wasn't as merciful, didn't try as hard to find a nonviolent way - or, didn't think that I should find a nonviolent way. All of those decisions were too far back to change, now. And the payoff for the choices I made was so impactful that I didn’t feel a need to go back. The next time I play the game, maybe I’ll choose differently, in an iterative effort to be attentive and considerate when faced with moral decisions - but for now, the way the story played out based on the choices I did make, that was satisfying.

And lemme tell you…“Skellige’s Most Wanted” is not the only quest in WITCHER 3 that has a weighty, well-earned payoff like that.

There was exactly one moment in SKYRIM that came close to that for me, during a quest called “Blood’s Honor”. I went out to kill a witch to get a special ingredient to cure a friend of being a werewolf, and while I was there I figured I’d kill all the witches, why not - and when I got back, I found that my friend was murdered by bandits because I was out so long. I was so genuinely upset that I did what you always do in Bethesda’s games when you encounter a tragic narrative development…

…load the my save file from five minutes ago and make a different choice (at which point I learned that his death was scripted anyway).

This is what I meant at the beginning of this piece when I said that the morality systems in games like MASS EFFECT or FALLOUT 4 or SKYRIM aren’t designed for stuff like self-reflection, no matter how good the dialog or whatever is. A well-written exchange can definitely get a player thinking, but in terms of gameplay: These systems aren’t made to be morally engaging - they’re made to be optimized.

There is an extrinsic motivator tied to your moral choice, whether it’s increasing your “Renegade” score or getting a funky skull, and you get immediate feedback on the outcome - so that, if you didn’t get what you wanted, you can easily try again.

In SKYRIM, this is then worsened by the fact that there is no delayed payoff for anything you choose. So instead of all my decisions adding up to a personal characterization of anyone, they just amount to a list of quests I finished and a list of quests I’m ignoring. There might be a lot to do in SKYRIM, but there’s very little to care about. And because you’re chasing these extrinsic motivators the whole time, the amount of investment you have in any one character or story tends to go down the more you play the game…and the more your hunger for gameplay pushes you towards sacrificing your character’s moral compass just to see what’s behind Door #2.

“Hey, just checking in again! So, do you want to kill one of your friends for no reason now?”