Silent Hill 4: The Room

A while ago, I did one of those chain letter games on Facebook, where for 10 days you post a video game you loved and tag someone to share their own list. With each game I posted, I tagged someone with whom I shared an experience or memory over that game.

I ended with SILENT HILL 4: THE ROOM.

I knew from the start that this game would make my list - and also that I would have no-one to tag for it. No-one shared this memory with me. The entire experience feels confined to my skull in a way that's difficult to express.

This sort-of review began as something in between trying to defend the game, gushing about what I think it does well, and telling some stories about my experience with it. Ultimately, though, I think this is mostly an attempt to reach out, to share this...thing inside me.

That's fitting - the game is, after all, about isolation.

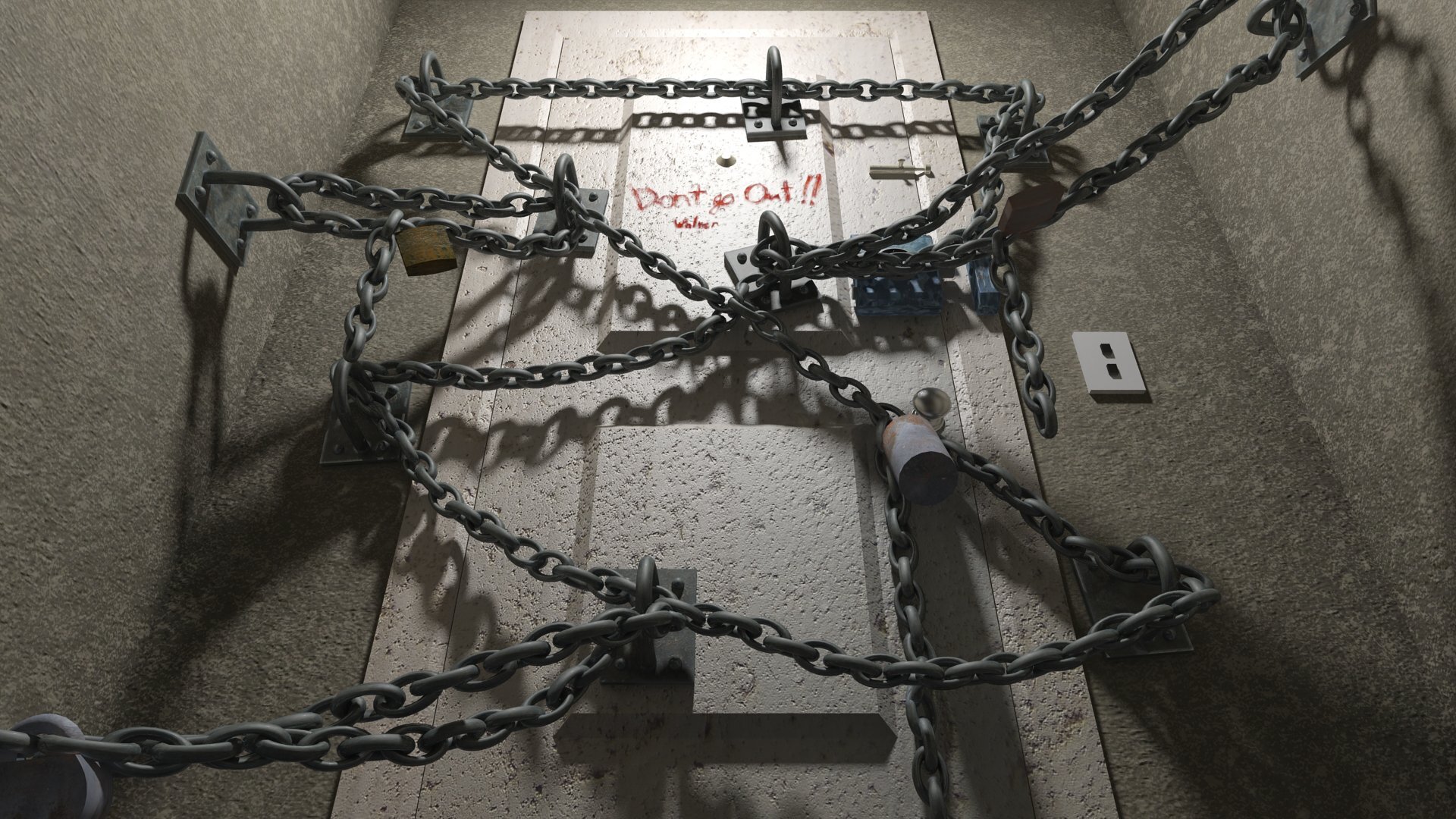

SILENT HILL 4, first released in 2004, is the final game made by Team Silent - the original creative group behind the Silent Hill games. In it, you control Henry Townshend, a man who awakens one day to find his front door chained shut from the inside.

The instantly iconic web of chains that keeps you trapped in SILENT HILL 4: THE ROOM

A portal in your apartment allows you to explore "worlds" - distorted versions of real places - but not escape the nightmare altogether. Cut off from the outside world while supernatural forces work around you to enact a horrific occult ritual, you travel to each "world" to try to learn its secrets and find a way out of your apartment, encountering monsters and grotesque histories as you go.

By the time SILENT HILL 4 came out, Silent Hill was a popular and well-established brand in survival horror games. The series didn’t quite have recurring characters (yet); instead, the identity of the games was tied up in the eponymous town of Silent Hill itself: a creepy, liminal space where memories and monsters force our heroes to face their anxieties and regrets. Unlike the previous three games, SILENT HILL 4 takes place outside of Silent Hill, but it is still very much connected to the town - starting to suggest that “Silent Hill” might not really be confined to a specific physical location.

SILENT HILL 4 might not be the best Silent Hill game, or the most important one. At the time of its release, it was not received especially fondly. As the years went by and several worse Silent Hill titles came out, recollections of the game have started to soften.

But I always loved this game. It is my Silent Hill game.

SILENT HILL 4 IS A BAD GAME

Each time I’ve tried to articulate why SILENT HILL 4 resonated with me emotionally as much as it did, I wrestled with the fact that, on the surface, it's not a very good game.

Most of the gameplay itself (not the experience, but what you are controlling the character to do) is combat, but the combat is clunky. Your character is stiff and imprecise, robotically swinging at the space a couple feet to the left of where the enemy is - kind of like an animatronic animal from a theme park ride. There isn't much depth to the combat, either. Most enemies don't have any AI worth talking about, and you don't have a diversity of ways to approach combat anyway - you beat most things up in the same ways that you do from the beginning of the game.

The focus on combat is weird, because it isn’t (strictly speaking) necessary to fight almost any enemy to beat the game. All you need to do to beat the game is find each narrative trigger (e.g. read this note, look through this peephole, walk near this door, etc.) for the next thing the game wants to show you. There are only three mandatory combat encounters: the game’s only two bosses, and an enemy that carries an item you need to progress. But you end up fighting a lot anyway, largely because you end up needing to pass through the same rooms often enough that it will just make your life that much easier if you just clear the enemies in that room (enemies don’t respawn). After a while, combat mostly ends up feeling like a chore (except for one major enemy type, which I’ll talk about later).

The game is deliberately repetitive, too. The only save point and inventory storage are located in your apartment, so you travel back to it constantly, which can break up the flow of exploring a level, and adds an unnecessary amount of tedium to managing your inventory. You also visit every level (except one) twice: After a major story event, you have to escort someone through each level that you cleared in the first half of the game. The revisits play out differently than the initial visits, with new enemies and puzzles for you to solve and new areas within the levels to visit, but a lot of it feels similar enough that it can get irritating - especially because of your escort.

The gameplay is honestly weak enough that I always hesitate before recommending it to anyone other than a die hard Silent Hill fan.

So how it did end up hitting me as hard as it did?

I’ve thought about this a lot.

I sometimes describe the game as being like a poem. It isn't just that the game is itself "poetic" - it's that the experience of it conveys a certain emotional state, and does so indirectly. The individual parts seem simple and at times incoherent when you examine them directly - whether it’s clunky mechanics, weirdly flat voice-acting, or an escort mission that lasts half the game. But the pieces all work together to make a mosaic message that is somehow both clear and aphasic. I can’t really describe it with words.

But I have to try.

MY HISTORY WITH THE GAME

I had a crush on Silent Hill for a while before I played any games in the series.

Around the time in my life that these games were coming out, my ability to learn about them greatly exceeded my ability to play them. I don’t remember for sure, but I think I might have been introduced to RESIDENT EVIL 2 by seeing an action figure for one of the game’s monsters in a toy store - after which I voraciously looked up everything I could about it. When my parents took me to book stores, I’d sit in a corner reading the strategy guide for NIGHTMARE CREATURES just to see the monsters and learn the lore (I never bought the game - or the guide). I never owned a PlayStation, PlayStation 2, or a PC that could handle real games, so I basically could never play most of these games during this golden age of survival horror. Somewhere in this period I discovered the Silent Hill series, and I was immediately fascinated by the creature design, and subsequently completely enthralled by the story and setting.

Then I went to college. And my roommate had a PS2.

My first semester at college was a weird time. I was already falling apart in all the usual ways (not showing up to classes, not doing homework), but that stuff doesn’t catch up to you until the grades go home - until then you’re just living with yourself, waiting for the same old shoe to drop, but trying to get through each day acting like it won’t. I was technically living away from home, but I was also still living in the same city, and still hanging out in familiar neighborhoods. That first winter got even weirder. Almost everyone in my entire dorm went home for the holiday break, but I stayed - and haunted the building by myself. In the midst of all this, a transit strike meant I didn’t even go into work. I would go for days at a time without seeing anyone other than the security guards at the front desk.

It was during this time that I finally bought SILENT HILL 4, the very first Silent Hill game I played.

I did little else. I ended up barely leaving my room. Shockingly quickly, my already-erratic sleep schedule slid into full-on nocturnal mode: I fell asleep at dawn, and woke up groggily an hour or two after sunset. Whenever I left my apartment, it was always too late in the evening to do anything I had meant to, like get food or buy appliances for my dorm room. It was like my entire life had a cold. I was living out-of-phase with the rest of the normal world around me, my waking experience mostly confined to my room.

Just like Henry Townshend.

Like I said before, Henry can “leave” his apartment through a portal - specifically, a hole that suddenly appears in the wall of his bathroom. (I think it’s no accident that this portal looks like a symbol of disrepair in one’s daily life.) Traveling through the portal takes you to a “world” that is a version of a real place (e.g. "subway world" is the subway station right outside of your apartment), but distorted in that typical Silent Hill way: floors caked in rust and blood, walls made of chain-link mesh and meat, and of course full of monsters. Other than that, these worlds only contain you, one other living person, and plenty of notes and items “left behind” by people from the real world - like everyone just left you alone in these places over winter break. Like someone dumped you into a terrarium full of sticks and leaves from your daily routines.

At the end of each of these worlds, the one other person stuck in them with you gets killed by the villain, and you get ejected back into your room, “waking up” in your bed. At first, Henry is unsure what to make of it - was it a dream? Did these things really happen? That may seem a little hokey, but it makes sense. I knew firsthand that if you spend long enough trapped in your room - in your head - you start to lose a sense of the boundaries between the remembered and the invented (a consequence of the erosion that happens when you stop tracking the passage of time for long enough).

I was living this game.

Both before and after that period of winter isolation, I would go for long walks around the city when I couldn’t sleep - by myself, wearing my headphones to insulate me from any other external stimuli. I would walk for hours from midnight to before dawn. And I was always drawn to places I'd been before: The place outside my high school where I stood at night, hoping to see the boy I was in love with leave after theater practice. The McDonald’s near my first job, where I would get dollar-menu items for dinner after work, when most of the other restaurants nearby had closed. The empty offices of my second job, where I wasn’t yet sure if I belonged. All sorts of different memories. At these hours of the night, the city was just alive enough that these journeys didn't feel inhospitable - I could get some caffeine in a bodega somewhere along the way, stop in front of the light of a storefront, hop on or off the subway - but also just "dead" enough that I didn't feel connected to anyone or anything outside me. Like the worlds that Henry traverses in SILENT HILL 4, I was walking through darkened, life-size dioramas of my own life.

A piece of graffiti barely catching stray light from a 24-hour bodega, from one of my after-dark walks. Photo by Mani Cavalieri

I was trapped in my head. The real boundaries of my confinement were not the cinderblock walls of my dorm room, but the bones fused shut around my brain. Habit can turn wide-open physical places into psychic cages.

For years after that, I was acutely fascinated with these mind-spaces in media (and still am, really) - from ROOM 1408 to HOUSE OF LEAVES - and, of course, everything Silent-Hill-related.

I sometimes wonder if the weirdness of that winter would've bonded me to whatever game I played. It's impossible to know, but I don’t think so. It certainly wasn’t the last time I isolated in my room with a video game until I lost track of time and space. Over the next several years, I played plenty more horror games, from DEAD SPACE and its sequels to ALAN WAKE to older titles like FATAL FRAME II: THE CRIMSON BUTTERFLY. These were all great, but I sank the most into the real time vampires. I would end up spending thousands of hours on RPGs like PHANTASY STAR UNIVERSE, DARK SOULS, MONSTER HUNTER TRI, and most of all SKYRIM. Some of these games left me with a lasting relationship to a new series; some were forgettable diversions; and SKYRIM ended up meaningful just by virtue of how much of my life I poured into it, even though I'm not on good terms with that game...kinda like a bad ex. But none of those fit with me the way SILENT HILL 4 did.

I may only have played SILENT HILL 4 for a fraction of the time I played SKYRIM, but sitting down and playing SKYRIM to escape (or, more accurately, avoid looking at) my problems, I still felt more like Henry Townshend than I did like a great dragonslayer.

getting in the goddamn robot

Maybe that's what all this is about.

SILENT HILL 4 is a lonely game. You explore nightmarish versions of real places that are near you. You are, in a sense, still a part of the real world - but at the same time, you’re removed from it. You can’t do anything in “reality”, you can only do things in these “worlds” that no-one else sees. You are an observer in your own life, living through a story that no-one else notices.

Let’s talk about what it’s like to be that person.

A common thread of criticism for this game centers around Henry Townshend. Between his strangely calm voice performance and a lack of apparent personality, he barely seems like a character at all. There is nothing noteworthy or significant about Henry; the only reason why the events of the game happen to him are because he happens to be the person living in this particular apartment (which has mystic significance to the villain). You don't know anything about his family, his loved ones, his friends - nothing. Henry wants to escape his apartment, but you never know what sort of life Henry wants to return to. You never get any messages from friends, family, or even employers asking where he's been - and Henry doesn’t seem to expect any. Is Henry going to get fired, or fail a class for not showing up? Does he even have a job? Does he have a life outside of his apartment at all?

Does he have a life inside of his apartment?

The only real piece of information we can find about Henry in-game is that he is a photographer, which we learn by observing the photographs which are the only decorations in his apartment. They’re all in black-and-white or muted sepia tones. Aside from a couple pics of Henry as a kid and one that was a gift from the building’s superintendent (another suggestion that Henry might not have that many friends), they’re all photos that Henry took himself, in past visits to Silent Hill. Memories that Henry kept revisiting until they enclosed him, even before the supernatural confinement that begins the events of the game.

Like most survival horror games, SILENT HILL 4 is full of notes - memos, individual diary pages left improbably accessible, scraps of paper with thoughts most people wouldn’t think to write down, etc. The notes you find depict people that you never meet, with more detail than the game ever provides for Henry. You learn about the personalities of total strangers: their fond memories, what they’re allergic to, who they love that doesn’t love them back, where they get their porn, who they find annoying, etc. No matter how banal or ugly or stupid these stories about the lives of others are, they are necessarily "better" than yours - because you have none. The Silent Hill games are traditionally all about learning some deep truth about your character, but SILENT HILL 4 is all about learning petty truths about everyone else. Henry is starved for human connection, and the game relates this experience to you by giving you an empty character and having you hunt down any scrap you can find of a real, lived human life. Even his dreams aren’t his: the recurring nightmare he has at the very beginning of the game is eventually revealed to be another character’s memory.

Jokes about Henry’s lack of explicit characterization and flat affect remind me a bit of the “get in the goddamn robot” jokes people make about Shinji, the main character of NEON GENESIS EVANGELION.

In the anime, Shinji is one of the only people capable of piloting giant machines used to fight monstrous creatures that threaten to destroy humanity - in other words, he is one of the only people who gets to save the world through heroic spectacle. And he doesn’t want to do it. His whiny, selfish reluctance to be the hero of his own show is regarded by many as obnoxious (one of my best friends loves to repeat that “Shinji is the worst”), and even characters within the show are frustrated and baffled as his recalcitrance. Who wouldn’t want to pilot these badass robots to save the world? And even if it were unpleasant, who would be that unwilling to do it in order to save the world? Just get in the goddamn robot, Shinji.

Shinji is fourteen years old. He was born one year after a cataclysm wipes out half of all human life. At age three, his mother died and his father abandoned him. While these things are important factors that shaped him, they’re not the only reason why people need to cut Shinji some slack. It’s not that his depression, insecurity, and loneliness are obstacles to him saving the world - it’s that the world is an obstacle to him facing these demons. And overcoming those demons seems as inconceivable and impossible as being asked to pilot a titanic bio-mechanical robot to save humanity from eldritch horrors. I remember reading an article where someone described the futility that you feel under the weight of what we now call “clinical depression”, saying something to the effect of: “If all I had to do to solve all of my problems and cure myself forever was just to press a button, I could not even do that.” That shit cut deep, and I kept that text with me so I could point to it and go “That’s what it’s like!” in the hopes that it could help others understand. Sometimes, dealing with these things seems so preposterous a task that you might as well ask me to save the whole world from incomprehensible monsters by myself.

Shinji wanders the streets of his city at night, isolating himself with music as he revisits the locations of his memories in EVANGELION 1.0: YOU CAN (NOT) ADVANCE

Shinji, like Henry, has very few outward signs of a lived life. When the series begins, he has no friends, no talents, and no apparent interests or hobbies other than occasionally going for long walks through a mostly-empty city at night, listening to music. The only thing about Shinji that other people say is valuable - the only thing in all of his personhood that another human being seems to regard positively - is that he can pilot these world-saving robots…a fact that arises mostly from an accident of his birth. The call to action comes with a cruel confirmation of Shinji’s lowest self-image: there’s nothing about him that he owns, enjoys, or is responsible for, that is worth anything. In the face of that, it makes sense to reject it. Even if it means forsaking the world. Even if, by rejecting the assertion that this is the only good thing about you, you are left with the conclusion that there is nothing good about you. At least that feeling is familiar. At least, this time, you chose it.

An aside

(Fourteen years after the original anime aired, the second installment of the “rebuild” of the series - EVANGELION 2.0: YOU CAN (NOT) ADVANCE - introduces the idea that Shinji is actually a reasonably talented home cook. He makes lunches for his friends, and they enjoy them enough that they fight over them - and are eventually inspired enough by them that, to do something nice for Shinji, they plan to cook meals for him. As someone who grew up with Shinji, even though what I’m seeing now is a reboot and not progression, I still feel proud of him. The modern update to Albert Cadmus’ exhortation that “One must imagine Sisyphus happy” has gotta be “One must imagine Shinji good at something”.)

The 2018 movie STARFISH begins with a young woman named Aubrey attending her best friend’s funeral, after which she breaks into her dead friend’s home and falls asleep in their bed. When Aubrey wakes up, she finds that a surreal apocalypse has occurred overnight, her whole town is deserted, and monsters are roaming the streets. A voice on the radio explains things, and tells her what she needs to do to save the world. After hearing this, the next thing she does is…turn the radio off, retreat back into her grief, and just…let the days wash over her as she stays inside, eating whatever’s left in the fridge and feeding her friend’s pet turtle. And honestly? That’s pretty fucking real.

Aubrey listens to mixtapes left behind by her dead friend, hidden in places where they shared memories, in 2018’s STARFISH

Asking someone to save the world - or even just to save one other person, as Henry is eventually tasked to do in SILENT HILL 4 - when they are in the unintelligible and inarticulable throes of grief or despair is something that you do to heroes in action movies, but in the real world, it don’t fly like that. Outwardly, the inaction of these characters can be incredibly frustrating. And it is. But inwardly? Why wouldn’t you resent the world that asks more of you, when you’re already facing the impossible? Being paralyzed - whether by depression or mourning or any other force - wouldn’t have consequences if it weren’t for the fact that reality cruelly marches on regardless of you. Time passes, and as a result, the unfair is demanded of the struggling. You are shaken to your core by the most powerful forces you can even imagine, and outside, things have the nerve to simply keep existing, as if nothing has changed at all. As William Finnegan so perfectly put it:

“You have to hate how the world goes on.”

SILENT HILL 4 begins when Henry wakes up one day and discovers that a cobweb of unbreakable chains and locks have impossibly appeared over the front door of his apartment, on the inside. Buried in the introductory exposition about this is a revealing detail: this happened five days ago.

For five days, Henry was just…living like this.

But Henry does eventually try to escape.

Aubrey does walk back out into the world, eventually.

Shinji, despite everything, does get into the robot. Over and over.

Maybe too late. Maybe after some important deadline passed, or some important relationship eroded, or things got worse some other way.

But they do try.

In an early scene, Henry sees his neighbors through his front door’s peephole. He bangs on the door and screams and shouts - one of his most vocal moments in the entire game - desperate to get their attention, literally crying for help. Of course, they can’t see or hear any of this - and so they assume things are fine, and leave him. Henry isn't fighting to break out of his apartment because he has something specific at stake that he's been separated from - he's fighting against being trapped, itself. He's literally fighting just to set foot out his front door.

This is some of what I mean, when I try to describe SILENT HILL 4 as poem-like. Henry is so outwardly under-characterized that trying to find his personality traits is like looking for something in a dark room - feeling around to find the contours and location of things by navigating the absence around you. And yet, the things missing from Henry still paint a picture of Henry. And it is, at times, an incredibly relatable and viscerally real picture. A picture that I want to carry around with me, so I can point to it and write long essays to try to say “That’s what it’s like!”

The game combat and and overall mechanics may, as one review put it, “have all the design wit of a dodo”, but there are few games that have conveyed this kind of human experience to me through their gameplay as powerfully and effectively as SILENT HLL 4.

SILENT HILL 4 is a great game

I guess it's possible that very little of this emotional resonance is by design. To some extent, that doesn't matter; even accidentally brilliant art is still brilliant. I’m starting to worry that you’re getting the wrong idea, though.

I've spent a lot of time until now talking about my attempts to understand how this game affected me by looking at evidence from my life and from related media, as though everything this game means to me were achieved in spite of the game itself - but to suggest that would be to do the game a major disservice.

Despite the very real shortcomings I mentioned above, SILENT HILL 4 has some really excellent and compelling creative elements.

A popular rumor claimed that SILENT HILL 4 was originally supposed to be totally distinct horror property, until Konami forced its developers to turn it into a Silent Hill game. This rumor has been repeated by haters and fans of the game for years. But Team Silent began working on SILENT HILL 4 as soon as they finished production on SILENT HILL 2 (at the same time as they began work on SILENT HILL 3, which isn’t as crazy as it sounds when you remember that 4 is a standalone title and that 3 is a direct sequel to 1).

This game has the same heart as its less-controversial predecessors in the Silent Hill franchise. To make the case in more specific terms, I want to touch on two elements of the franchise that are beloved by fans: enemies and music.

THE ENEMIES

The “lying figure”, which first appeared in SILENT HILL 2 (2001)

In the early Silent Hill games, most of the monsters you find are representations of pain. Their designs themselves generally don’t communicate danger - they tend not to have visible teeth or claws or weapons - so they’re focused more on unnerving. It’s a natural empathic response to be uncomfortable in the presence of something with recognizable human elements that appears to be suffering. One of the most enduring designs from the series is the “lying figure” - a humanoid trapped in a straightjacket made of its own skin that also covers its face, its arms uselessly stuck over its chest and its head writhing desperately in search of a breath of fresh air. Rather than threaten us with bodily harm, these designs threaten to confront us with something unpleasant - which is a particularly great choice, since that’s what these games are ultimately about: facing horrible truths that we carry around but refuse to look at. SILENT HILL 4 continues this trend of anguished antagonist, most prominently with a type of enemy literally called “victims”.

These victims are the “ghosts” of people killed by a supernatural serial killer (the game’s villain), who are now trapped within the strange worlds that you explore. Each victim is unique, and there are at least 10 total that you encounter throughout the game. Unlike other enemies in the game, these ones just look like people. Also unlike other enemies in the game, they can’t be killed. They can attack you, but just being near one causes damage - Henry will clutch his head in pain, a grainy red filter will start to cover the screen, static will overtake the soundtrack, and your health will deplete. These victims also pursue you to a greater extent than regular enemies: the latter are confined to a single room, but ghosts will chase you throughout a level - and, eventually, from one level to the next. They can crawl through walls, so there’s no limit to their ability to pursue you. You can fight them, and hurt them, but the most you accomplish is knocking them down for a brief period. Then they just get back up, and come after you.

The most dangerous enemies in SILENT HILL 4 are dead bodies in pain

As I mentioned before, the gameplay is all about combat. All of your weapons will degrade over time: Your melee weapons gradually break, and your gun will run out of ammo. So, the main challenge posed to you is to figure out how to manage your weapons and healing items to get through each world. (This game doesn’t really include the sorts of logic puzzles that featured in the earlier titles.) But although your resources in this game are finite, the threat posed by the ghosts is not. No matter how proficient you are with the game’s combat, the ghosts are here to remind you that you are ultimately not in control. This dynamic has two major thematic functions. First: Having an unbeatable pursuer is a great way for a survival horror game to turn up the tension and panic. Second: Going back to the themes of depression and isolation, it makes avoidance a core part of the gameplay - again, making you play out the cognitive patterns that come with the emotional experience the game is relating to you. You are faced with problems that you can fight, but you’d rather avoid even looking at…which doesn’t stop them from continuing to follow you. This feeling gets deepened repeatedly as the story progresses: In each world, the person you meet is eventually killed in front of you, becoming another victim…another ghost. Over time, your failures add up - haunting you, and inviting further failure.

This isn’t the first game to feature persistent enemies that pursue you throughout the game, nor is it the most polished implementation of that sort of thing, but it is still pretty unique. Unlike many other examples of this sort of mechanic, there’s no scripted evade-the-ghost sequence, nor any battle where you confront them head-on and end their threat for good. (The closest you get to this is a special sword that, if used on a ghost, leaves them pinned in place. This doesn’t kill them - they get right back up if you pull it out of them. You get one of these “for free”, and can find up to four more…which still leaves you with twice as many ghosts as you have “solutions” for them.) The ghosts are central to the experience of SILENT HILL 4, but they rarely have the spotlight. Rather than feeling like a gimmick or a setpiece, they feel like an outgrowth of the setting of the game - another expression of the themes and feelings of your environment. It’s not that there are enemies that hunt you down, it’s that you’re in a world that you cannot escape.

THE MUSIC

Fans of the series already know what I’m going to say here:

The music in SILENT HILL 4 is fantastic.

One of the celebrities in the Silent Hill world is series composer Akira Yamaoka, an original member of Team Silent who went on to score two more Silent Hill games after the team disbanded. As much as the monsters, Yamaoka’s music is synonymous with Silent Hill - so much so that the 2006 movie adaptation SILENT HILL is exclusively scored with pieces from the official soundtracks for the games (except for one Johnny Cash song near the beginning, partly used for a gag).

It’s not just that Yamaoka’s tracks themselves entrancingly moody - it’s also the way they are made, and then woven into the game. Yamaoka has said that he will sometimes score the games “backwards”: He will identify the moods and tones that are core to the game, then start banging out tracks - and once development of the actual game itself gets far enough along, he’ll look at the scenes in the game and see which tracks he made that would best fit it. As strange as this approach sounds, it works - partly because Yamaoka is allowed to be one of the creative leads for the games from the start. One of the things that made Team Silent’s titles so compelling is how much the team worked in unison, allowing a single consistent vision to permeate every aspect of the game - from creature design to level layout to soundtrack. There are parts of SILENT HILL 4 that may be clunky, but there are no parts that are very far out of sync.

An aside

(One side effect of Yamaoka’s production process is that he ends up making a lot of great tracks that don’t actually end up in the game. These pieces are nonetheless still included in the official soundtrack, intermingled with the tracks that did make it in. Because of this, you kinda feel like these “unused” tracks are still somehow part of the text of the game itself, in a way - or at least, a sort of paratext - that gives the impression that the world of the game is bigger than the game you experienced. What’s even better is that because these are musical pieces, this paratext basically can’t be transcribed in some fan wiki somewhere that wants to carefully catalog every aspect of that game world. It remains fluid and personal to each listener.)

We also need to talk about which moods the soundtrack of these games is highlighting. For a series that has always been about horror, relatively little of Team Silent’s soundtracks are trying to communicate horror - at least, in the conventional sense. To set up a quick point of comparison, let’s check out the soundtrack for 2008’s DEAD SPACE, an action horror game in the vein of RESIDENT EVIL 4 which I happen to love dearly. This is a good soundtrack for a great game. But if you skip around through it, you notice that a lot of it starts to feel samey - not because the pieces are that similar to each other, but because they’re all trying to convey the same thing: something between “Oh fuck!” and “BOO!”.

Now, don’t get me wrong - Yamaoka still makes pieces intended to be scary for portions of the game. But “scary” (or even “horrifying” or “disgusting”) isn’t what most of the soundtrack is about, even in moments of the game that are meant to be nasty. The original 1999 SILENT HILL features a scene where a character discovers that they have already died, and are just a memory that exists in a nightmare world. As they have this revelation, their body begins to fall apart, blood streaming all over them while they stumble towards the hero, begging for help, only for the hero to run away in horror. The soundtrack for this scene, “Not Tomorrow”, is not horrific at all - instead, it’s sad…and, surprisingly, hopeful, if a bit plaintively so. SILENT HILL 2 features a major boss fight set to “Betrayal”, a piece that is equal parts reverent (maybe celebratory?) and industrial. In SILENT HILL 3 your dad gets murdered, and after you kill the monster that did it, you’re treated to the enigmatically named “Never Forgive Me, Never Forget Me”, a contemplative and mysterious track.

SILENT HILL 4 gets even stranger still. After the villain attempts to murder one of Henry’s neighbors, there’s a scene where Henry finds a wall full of photos showing that the villain had been stalking this neighbor for some time, and recent photos showing that she survived the murder attempt. This scene is set to “Fortunate Sleep”, which is playful and…kinda snazzy, like someone’s up to something. Are we supposed to feel delighted, despite everything? Later on, you’re exploring a version of your apartment building made of rusted pipes and twitching meat, as you experience memories of the villain’s cruel father. In the background, “Resting Comfortably” plays - a soothing, peaceful tune that is strongly reminiscent of “Serenity”, the track used for typewriter rooms in RESIDENT EVIL 4 (i.e. a soundtrack used by an action horror game to tell you when you were in a place that was guaranteed to be safe). Is there something relaxingly familiar about these terrible visions? Hell, the first music you hear over the starting menu is “The Last Mariachi”, which, as someone who’s thought about this game an incredible lot for many years, I just gotta tell ya…I have no idea what that means. What mariachi??

In the words of Detective Benoit Blanc from KNIVES OUT:

That is, even though these soundtrack choices are unconventional and unexpected, there’s nonetheless something about them that works. We’re not dealing with a situation like DEADLY PREMONITION, where a limited soundtrack was stretched over an entire game, resulting in already ridiculous scenes becoming insane as they do things like “use the same soundtrack that accompanies murder scenes in a conversation about recommending a weird sandwich”. As I mentioned above, Yamaoka’s soundtrack coheres - both within itself, and with the rest of the game. It was, after all, made with a focus on exploring the feelings core to the game. It’s easy to get lost in these tracks, because they don’t serve any master other than those feelings.

Having the soundtrack emphasize non-horror moods, like “melancholy” or “comfort”, gives the game a strange sort of charisma. It brings you past evaluating what’s going on in strict terms (e.g. “Am I in danger?”, “How threatening is that monster?”, “Do this character’s actions make sense?”), and into following a sort of dream-logic - where the mood defines how you look at the game more than anything else. It makes you feel at home in this horror, the way the your sweat-stained bed with its dirty sheets is still comfortable, even as your apartment is a mess and your life falls apart around you.

Our special place

“It’s covered in blood and rust...this is my room...”

Let’s bring all this home.

The defining element of the series, repeated in every Silent Hill property, is that the town of Silent Hill transforms between different versions of itself. There are at least three, in theory:

The “real world”, where Silent Hill appears as a normal town with residents, a charming lake, and even a theme park

The “fog world”, which is mostly the same place but covered in an unnaturally thick fog and abandoned except for monsters

The “other world” - an overtly horrific version stuck in permanent night, where the buildings and streets become as warped as the monsters that roam them

As you play a Silent Hill game, your setting will shift from one to the other, back and forth. Except you never actually see the “real world” Silent Hill - it only exists in implications and memories.

In SILENT HILL 2, your character once spent a weekend with his wife at the town’s lakeside resort, so they’ve been to the “real” Silent Hill. You even see a video from the trip. The memory is dear to both you and your wife; she tells you it’s “our special place”. That’s why you go back to Silent Hill. But the version you return to blanketed by fog, and as you wander it, you become unsure of your memories.

The first four Silent Hill games have a consistent, distinctive visual style for the “other world”, one typified by blood and rust. But it isn’t just that it’s gory and metal - that would just be a pretty bog-standard horror setting. What makes Silent Hill's “other world” memorable is that it’s based on normal things. The other world is, essentially, just the real world - but with its materials replaced. Picture the area around your bed at home, but your surroundings are made of rusted metal, skin, and flesh - instead of wood, metal, and plastic - all still in the same places, all having the same shapes.

SILENT HILL 4 takes this a step further. The different "worlds" you travel to are already part-real-world, part-other-world. Some of the locations are so inherently monstrous that they barely have any “other world” elements at all - like a prison for orphans. Others are so consumed that they’re almost entirely made of twitching meat. There's no transition and there’s no distinction. This blurring of lines reinforces the erosion of boundaries going on in Henry's head as a result of his isolation. It also reflects the reality of being a Silent Hill fan. We’ve never seen the normal version of Silent Hill. For us, the desolate and gruesome versions are our special place. And we keep going back.

I often hear people describing the pervasive mood of these games as “burrowing into you”, but I think it’s the other way around: you burrow into it.

You find the comfort in the horrible.

Shinji sleeps in garbage, still listening to his music, during a night ramble in EVANGELION 1.0: YOU ARE (NOT) ALONE

A small child, contented to be home, lays down on a filthy couch in a haunted apartment in SILENT HILL 4: THE ROOM

This is what takes you from "being trapped in your room" to "being trapped in your mind": a world where the walls of your home are actually made of the meat in your head. There's no longer any distinction between the physical and mental space you inhabit.

And at the same time as what you're feeling inside is all around you at all times, literally plastered on the walls and ceiling and floor, other people just can't see it. In the game, you frequently look out the peephole on your front door, and you see handprints smeared on the wall opposite your door. The handprints track the body count of the game’s villain - but no-one else can see them. You are isolated in your understanding of the world; there is a permanent and impenetrable barrier between your experience and that of others.

All of this culminates in one of the best twists I've ever experienced in playing a video game - what finally happens when you manage to open the door to your apartment.

For sixteen years, this game was only available in its original format, i.e. for the PC, PlayStation 2, and (original) XBox. And as much as I loved it, I had no way to re-play it, so I was just wading through soundtracks and drinking stale memories that I refused to throw out.

But it just got re-released for PC (like a cosmic joke, in the middle of a pandemic in which many of us find ourselves trapped in our homes by invisible forces). And considering how old this game is, computers that can run it are more commonplace now than they were when I was sitting in bookstores reading strategy guides for games I couldn’t own. If you want a slow-paced, introspective horror experience, one so atmospheric it almost verges on meditative at times, then your special place might just be here, in the blood and rust.

Despite the game's flaws, I encourage you to play it.

Or watch a “Let's Play” video by someone who was also heavily engrossed in the game, and experience it vicariously through them.

Or listen to its soundtrack on loop, maybe as you wander your streets at night. Like I still do.

I'd love you to experience it, somehow. That's ultimately why I wrote all this, I guess. Why I felt the need to try to articulate this personal, almost private, appreciation of this game.

I want to see if I can break out of my apartment, and share this experience with you.